You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘social entrepreneurship’ tag.

Tag Archive

ROI’s Dirty Little Secret

July 7, 2009 in Uncategorized | Tags: finance, measurement, metrics, ROI, social entrepreneurship, social impact | 3 comments

The term “ROI” just might be the most hackneyed and disgusting piece of vocabulary in the world of organizations.

I hear it on a daily basis in my work life and have watched it spread throughout the blogosphere like a bad virus. Ask anyone to put their “metrics hat” on and they will invariably drop the word “ROI” on you, often in a desperate attempt to build their credibility and sound more like a CFO.

There is no ill will here – I am intentionally being provocative – but there IS (and probably always will be) an enormous need to increase the level of statistical/financial competence among professionals who strive to measure impact, whether financial, social, environmental or otherwise. We can’t simply borrow from existing concepts and measures without understanding their dirty little secrets.

So let’s talk about ROI and its dirty little secret.

ROI, or Return on Investment, is a decision measure. By that I mean that it is supposed to give you an indication of how successful an investment decision has been/might be. The most perfect example might be your stock or 403(b)/401(k) portfolio. When you make the decision to funnel dollars to those accounts, you are placing a bet on the success of the fund or company whose shares you are purchasing.

So…. you invest, time passes, lots of stuff happens (with the company, economy, etc.), and then, at some point, you decide to see how well your bet paid off. Were your right and/or lucky enough to see a positive ROI? You subtract the original value from the present value, then divide by the original value. TA-DA!… ROI.

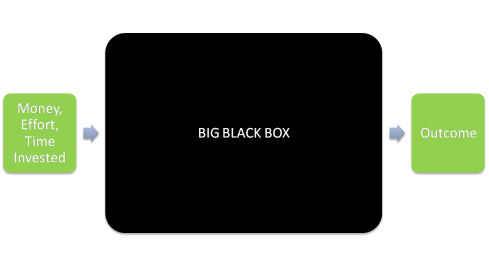

Not rocket science, right? Which is probably one reason it is so well-liked as a measure. But let’s take another look at that process. Here it is visually.

One of the major and perhaps most overlooked problems with ROI is that it only cares about the green boxes – the inputs and the outputs. This is fine if you’re an investor, since you often don’t care so much about what generates the returns as the fact that they are there. Remember, it’s a decision measure – did your bet pay off? – that doesn’t discern skill from dumb luck.

But what about the Big Black Box? All of the “stuff” that happens between the time the investment is made and the point in time in which you’re measuring ROI? Doesn’t that count? If you run an organization or care at all about a company’s internal operations and how it is generating returns, then YES, ABSOLUTELY! It counts an enormous amount. In fact, if you’re trying to measure social impact, unless you understand what’s going on in that Big Black Box and how it correlates with outcomes, you simply cannot say with any confidence whether what you’re doing is having an impact. Period.

So please, please, use ROI with care. You, your organization, and your constituents will be better off as a result.

[Esoteric aside: I’m referring to a very specific form of ROI here. If you report on ROI as “people served per dollar spent,” or something to that effect, know that that’s a great thing to measure as an indicator of operational efficiency or effectiveness but not true ROI. You might be confusing people or damaging your own credibility among shareholders and donors by referring to it as such.]

“Beyond Good Intentions” and Not Fearing Profit

July 6, 2009 in Uncategorized | Tags: design, innovation, social entrepreneurship | Leave a comment

As follow-up on my last post, I wanted to share part of Tori Hogan‘s “Beyond Good Intentions” series.

Tori is former aid-worker, filmmaker, and blogger with SocialEdge.

Episode seven of Tori’s series explores for-profit approaches to development in Madagascar with the company BushProof.

In addition to the ingenuity of the founders and employees of BushProof, what’s striking about the video is the fact that Adriann Mol, Founder and Director of BushProof, is not ashamed of the fact that he is running a bona fide for-proft business, albeit one with a very explicit social mission that guides its management principles.

To paraphrase Adriann:

“…You enter into an economic system that gives full sustainability… So it saves these people significant money… it gives us income so we can run the company and grow bigger, sell more of them – it’s a win-win.”

In Defense of Profit OR Separating the “Social” from the “Entrepreneurship”

July 2, 2009 in Uncategorized | Tags: entrepreneurship, fast company, ford, google, NGO, non-profit, social entrepreneurship | 2 comments

I have been pondering this blog post over the last several days, only to find that I’ve been beaten to the punch by Nathaniel Whittemore at Change.org and Theresa at the subjectverbobject blog. (And, much to my pleasure, Nathaniel’s post was prompted by a fantastic Fast Company article titled, “Rwanda Rising” – check it out.)

Here is Nathaniel’s quote that is sparking interest and debate:

1. The difference between “social entrepreneurship” and “entrepreneurship” can break down quickly. When we’re talking about African students building new web applications to make it easier to send money to families back home, what should we designate that? Entrepreneurship or Social Entrepreneurship? Or does it not matter? Should it perhaps make us wonder if we should instead be holding up that type of work to argue that real entrepreneurship is about the creation of all types of value – not just about financial wealth. In other words, maybe our view should be about the inseparability of “social” from “entrepreneurship,” and perhaps that’s easier to understand in the emerging market context.

Indeed.

To add a bit of my own perspective… I became aware of the concept of social entrepreneurship back in 2005, while carrying out research in Colombia. Disheartened by the limited amount of management expertise within the NGO community and the lack of clear accountability in how aid dollars were being spent, I found myself strangely gravitating toward for-profit, purpose-driven enterprises.

Really, the change was weird for me. I had spent most of my college days being suspicious of corporations of any size and disgusted by economics and its profit-maximization principles. I questioned economic globalization and modern-day capitalism. Yet, as I grew increasingly disillusioned with life inside non-profits (NOTE: I do recognize that there are many outstanding, well-managed non-profits out there!), I began to truly appreciate the incentive systems that exist in the free market and within for-profit organizations.

In fact, an unwieldy and mildly disturbing appreciation for the concept of “profit” itself began to bubble up from deep within me. I realized that profit, despite its sullied reputation, plays a hugely meaningful role in the life of corporations.

Profit is, for most companies, a measure of the overall health of the organization. It is the final word on 1) whether you are producing products and services that people value enough to actually pay for and 2) whether the organization is being managed effectively and resources stewarded efficiently. In this sense it truly is the “bottom line.” And of course profit and, more specifically, free cash flow are also the forces that enable growth. Conversely, lack of profit resulting from mismanagement and/or creative destruction eventually leads to the dissolution of the corporation and allocation of resources to where they can be put to better use. Generally speaking, all good things.

But once we recognize that profit is not inherently evil or something to be minimized, the concept of “social entrepreneurship” starts to break down a bit. What makes an enterprise “social” if not some aversion to profit or, at least, strict prioritization of doing social good over making money? It can’t simply be the desire to bring about change or have a positive social impact. By those standards, some corporate behemoths might even be (or once have been) considered social enterprises.

Take Google and Ford as examples.

Sergey Brin and Larry Page were HUGELY suspicious of traditional corporations when they started tinkering with the PageRank Algorithm. Google was born in part out of their disgust with content portals like Yahoo, who gave the best real estate to the highest bidders, and search engines that were centered around paid-for results. Since day one, they have aspired to make readily available the entire world of information to anyone and everyone who might care enough to look for it. They dreamed of democratizing knowledge and, indirectly, knowledge-creation, and that’s exactly what they’ve done. In the process, they’ve made billions of dollars and grown at an incredible rate.

Ford, on the other hand, had a dream to make an automobile that the average working American could afford. Before the Model-T, automobiles were toys for the rich and famous. In addition to being superior modes of transport, they were conspicuous signs of wealth and privilege. In a sense, the success of Ford democratized movement. And his foresight in understanding that employees can be customers also led him to offer unprecedentedly high wages to Ford assembly-line employees.

So are/were Google and Ford social enterprises? If they once were but are no longer, at what point did they cross over to the dark side? Where do we draw the line between social entrepreneurship and plain-old entrepreneurship. Should we even attempt to define that line?

To the last question, I say “no,” and for two reasons. First, who’s who will be self-evident the majority of the time. Secondly, and more importantly, trying to carve out a world for social enterprises vs. “other” enterprises will only serve to reinforce what is a false dichotomy and feed our aversion to valuable ideas like “profit.”

Rather than looking for better ways to categorize and attach labels, let us strive to create a world in which enterprises in general serve the needs of society while behaving responsibly.

Recent Comments